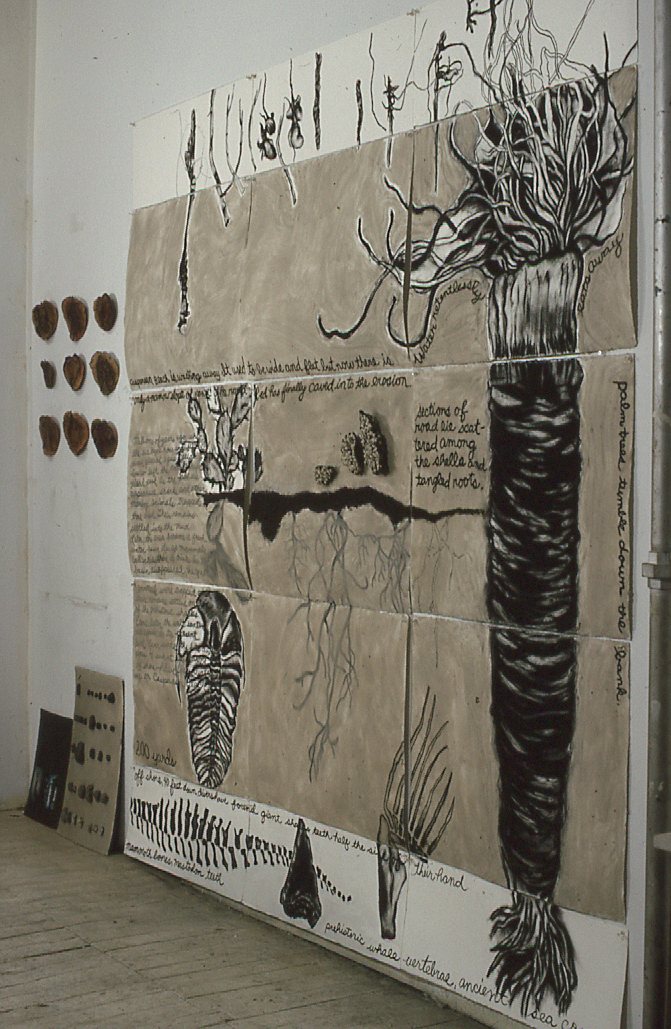

CASPERSEN BEACH IS WASHING AWAY

By Alyson Pou

There are some places in this world that I always want to go back to.

There is something about them. There is a dialogue, a conversation I want to have. It’s sort of like being with a person. I want to be with the place, understand how all the parts fit together, or more precisely just get to know some of the layer. How does it fit together?

There’s a shallow curve in the river that runs along Highway 9 near Cummington, Mass., a small waterfall tucked in the woods outside Straudsburg, Pennsylvania. And then there is Caspersen Beach near Venice, Florida. I remember the first time I ever went there in 1977. It was just about sundown, the narrow road was almost completely covered with sand slowing in hard waves across it, and as we drove we could get little glimpses of water through the dunes and underbrush. Walking over the dunes, out on to the beach my companions were in deep conversation about the plumbing business in South Florida. Bored, I walked away and down the beach. Playing chase with the waves, teasing, calculating, walking right to the edge – Jumping, hopping, running so the water couldn’t catch my toes. That’s my memory: everything was dusty rose and pink. The waves, the sky, my legs – jumping and hopping and twisting and running – looking down the beach, for miles nothing but sand and water and the sound they make together. It would be ten years before I came back.

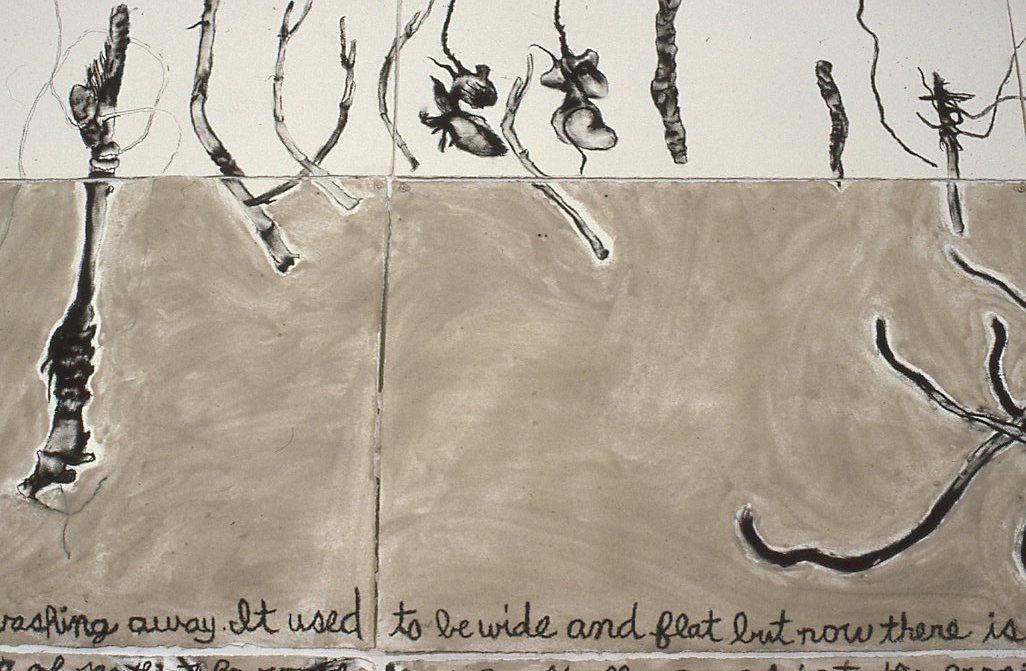

Caspersen Beach is washing away. It was already washing away that first time I visited. Big changes were afoot. The community was and is very upset. Some of the people remember the days when the sand stretched out lazy and flat for yards and yards. (Easy to park, easy to walk. Easy to stretch the Chezlounge and picnic). But I am not upset. I am excited by the change. There is no deception of permanence. There is a clarity, an honesty about the forces at work. When the tide is out you can sit. When the tide comes in you must retreat, pinned to the ledge of dying roots and twisted palms. You have to give way to the cycles of the water. Even the asphalt roadbed, which used to be ¼ mile back from the beach, is giving way. Huge sections of it dangle above your head in suspended motion on the ledge of the land. Palm trees in varying states of decay tumble down the banks, rolling twisting in the surf. At low tide sections of the road lie scattered among the shells and seaweed along the narrow sand.

But right now, I haven’t seen this beach for ten years. I’m just off the plane from a NY winter and Gail is driving me straight to the water for a midnight swim. Full moon is tomorrow. As we strip and make piles of our clothes, we can easily see up and down the deserted beach. As we wade into the water, I am covered in chill bumps. My skin shocked at the long delayed exposure to open air. Gail says, “You know, people always warn me about swimming late at night. Sharks like to come in close to the shore late at night for feeding. Late at night, the schools of small fish and warmer water attracts them.”

Oh great! I think, here we are on a beautiful night, warm tropical air, I just spent a ton of money to get here and she starts talking about sharks! We might as well be sitting around some woodland campfire freezing to death telling stories about the werewolves. It’s dark, the moon is full (almost) and some creature with sharp teeth is coming to eat us!

“They are really attracted by the kicking and splashing,” says Gail. “I’ve heard they can get trapped between the sandbars and beach at low tide. It’s low tide you know. We are in between the sandbars and beach you know. Last year, a man was swimming the channel and he crossed the path of some sharks in a feeding frenzy; there was nothing left but a bloody pulp when the guide boat, which was only yards away, reached him. He never had a chance.”

Swimmers drifting out too far on rubber rafts, vacationers losing arms and legs just because they were splashing around having fun. The stories got more gruesome. I circle closer and closer to shore.

Most sharks can’t breath if they aren’t moving. They have to move all the time because they don’t have the air sack, which allows bony fish to sort of blow up and just hang in the water. They are committed to a life of constant motion. Sharks, as a species, are the oldest inhabitants of the hydrosphere. Sharks are ancient. They first appeared about 400 million years ago and have evolved very little since that time. 400 million years ago! That is almost 200 million years before the dinosaurs first walked on the earth.

(I always thought you had the void, then the amoebas swimming in the void, then the giant dinosaurs. Sort of a micro to macro Big Bang.)

But, come to find out, lots of things and million of years happened in between. If the whole of time were a calendar year, dinosaurs appeared sometime in December and human beings appeared about 11 or 11:30 on December 31st.

We human beings are fascinated by ancient things, things we don’t remember or can’t understand. We fear them. We make a big deal out of them. We make up extraordinary stories, legends, and myths to scare and reassure ourselves. The same themes over and over, generation after generation, to try and explain the unknown.

Recently, I went to the library looking for legends and shark lore, maybe some gruesome shark attack stories. And the reference librarian, checking it out on his computer said, “Nothing about shark attacks, but what about shark wrestling?”

“You bet”, I said. “Who needs old legends when you can get the real thing.”

So, I went over to the junior section and pulled a book called, “The Man Who Rode Sharks”, an autobiography by William R. Royal. Turns out Mr. Royal lives in Venice, Florida. That’s where he wrestled his first shark and he’s the great uncle of Scott Egelfield, the guy with the plumbing business who took me to Caspersen Beach that first time.

Here is how Mr. Royal first wrestled a shark. During the Great Depression, he fished everyday off the Venice Bridge, in order to feed his family. Eventually, hoping to sell surplus catch to the local market, he devised a new way to go after the bigger fish. He designed a harpoon of galvanized pipe with a welded trident head and learned how to accurately throw this harpoon from the bridge. Sometimes, if his catch was going to get away or cause him to loose the harpoon, he would jump off the bridge, tie a rope around it’s tail and swim to shore. One afternoon, while he was patrolling the bridge watching for fish shadows around the pilings, someone spotted a 7 ft. long lemon shark. Excited at the possibility of pulling in such a large catch, he lifted the harpoon overhead and hurled it with all his might. BINGO! It struck the shark just behind its head and all hell broke loose. The water exploded. The shard almost yanked both Royal’s arms out of their sockets as he tried to hold the rope. It was clear he must act or lose the harpoon. So he jumped into the water, intent on tying a rope around the shark’s tail. After a long struggle, Royal managed to slip the rope around the shark’s caudal fin.

“When the fish hit the end of the line and could go no further, he turned and headed toward me…” Here is how Royal described it:

“He lunged for me. I butted him away with the harpoon. He slid past, turned and came back. Again I fended him off. Finally, he swam to the end of the rope, seemed to lose his fight. Exhausted myself, bloody from being thrown against the barnacled pilings, but still keeping away from his head, I passed the harpoon up to eager hands on the bridge and yelled ‘Haul him up’”.

“While I clung to a piling, the twisting, thrashing, body slowly rose tail-first from the water, glistening and heavy as it inched past me. And there we were, eye to eye. As long as I live, I will never forget that yellow eye with its almond-shaped black pupil and nictitating membrane. I realized what kind of animal I had so carelessly jumped into the water with. As I crawled onto the beach, I thought only of the feast he was going to make for my family and friends, thankful things weren’t the other way around.”

Back on shore, after our midnight swim, my senses are heightened. I feel the humid breeze on my skin; begin to smell the salt air and minerals in the water. Sharks really are amazing creatures. All of their senses; sight, smell, touch are incredibly refined. They can smell a tiny drop of blood in the water a mile away. The can hone in on and stalk their prey using this weird radar called the bioelectrical sensory system. This system consists of several jelly-filled canals and hundreds of skin-pores called the ampullae’s of Lorenzini. And it is scattered across the front of their head and down the sides of their bodies.

Now, every living creature produces an electrical impulse, every living thing has an electrical field around it. So it is impossible to hide from sharks, because that is what they hone in on, the life force. They can find their prey without seeing or smelling them. They can sense a stingray or flounder buried in the sand and strike with great accuracy. No wonder we put them in a scary, mythic category with werewolves and vampires.

Don’t swim with your dog. Don’t bleed in the water. Don’t carry around a dead fish for very long. Don’t wear shiny jewelry. Don’t get in the water in your tan is uneven. Don’t wear a bright swimsuit—No red, yellow, orange – No stripes. No two-toned suits, dark on the front , light on the back, you look like dead prey. Don’t pull a shark’s tail and don’t try to catch a ride. Look around before you jump off the boat, and please surfer no belly boards.

But why do sharks attack people? Maybe they mistake us for fish. (They don’t actually eat people even after they’ve bitten, they just spit us out.) Maybe they are defending territory. Maybe they are flirting, making an advance of courtship.

I am staying down the intercoastal waterway from the beach on Gail and Derrold’s sailboat. Gail lives on the boat year-round while Derrold goes on expeditions to China and Africa. They built every inch of the Phoenix – inside and out – by hand. (It took more than ten years.) The fifty foot steel hull is of Scandinavian design and the boat is equipped with radar to handle the open sea, cross the Atlantic, sail around the world.

Derrold learned to weld steel, apply fiberglass, read navigational chars, laminate wood. He learned how to build and maintain motor and pumps. Gail went to nursing school to prepare for a career she could use internationally, knowing also that medical skills, like treating shock and giving injections, are a necessity at sea. She constructed the interior floors, bulkheads, and kitchen and storage cabinets. Every piece of wood chosen and cut precisely. Every brass latch and hinge mindfully placed.

The Phoenix has risen completely from their vision and determination. Every part of it shows the presence of their hand and this is what I love about it.

Sitting on deck, my second night in the marina, I hear crickets and cars. Is that heat lightning or thunder squawl, to the north behind the bank covered with sea grapes? A bird cries…an orange cat runs down the pier. The boat strains against its rope. A breeze whips up and now the lightning explodes across half the sky. I climb the mast expecting a storm, and still the stars are everywhere.

Below, the boat’s ribs are fine polished mahogany. I roll over on the narrow bunk and press my body against their curve. Listening for rain, I hear the snap and crack of tiny brine shrimp against the hull.

At some point, millions of years ago. Most of this country was under a shallow sea. When the water receded during an Ice Age, the area around Caspersen Beach became a huge tidal pool, trapping sharks and other marine life. They died and settled into the mud. Eventually the area became a fresh water-basin. As this basin disappeared, the great mammoths and mastodons that drank there were trapped and their remains settled on top of the prehistoric sharks. Eons later, the salt-water rose again to its present level, covering this prehistoric graveyard. Ever since, the bits and pieces of what lay buried just two hundred yards off of Caspersen Beach have been washing ashore. Scuba divers have found giant shark teeth the size of my hand, ancient tree stumps, mastodon teeth and mammoth leg bones mixed with ribs of ancient sea cows and whale vertebrae.

“Full Fathom five thy father lies, of his bones are coral made.

Those are pearls that were his eyes; nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change into something rich and strange.

Sea nymphs hourly ring his knell.”

William Shakespeare

Late afternoon, shapes and colors begin to soften from white to gold. I am standing for a long time, scanning the water’s surface, imagining the layers of time below it. Then, my eyes race on to the horizon and rest there.

Ancient teeth, bones, rocks, freshly dead fish, shells and seaweed all washing up around my ankles – roads, palm trees, roots, cactus and dirt all washing out to sea. All crossing and mingling right there, right along that edge where water meets land.

I say to Gail, “I am sure the angels live here. Right here along this edge. I hear them.”

She says, “Of course, angels always live in the place between. After all, they are messengers. They are always bearing news and bringing answers, traveling between heaven and earth, earth and water, the living and the dead, us and ourselves. They always live on the boundaries, at the edge. I see them everyday along the squiggly iridescent line of the horizon. Look! Their wings beat the tips of each wave as it touch land for the first time.”

The next day, I find a large batch of discarded calico wings – muted brown and white, mismatched, sort of familiar and worn. Of the mollusk family, once housing a soft gray fluid body. Somebody named them “arc shells”.

Arc: the apparent path of a celestial body as it rises above and falls below the horizon.

Now, on my last day, just after sunset (it’s twilight). I turn away from the approaching dark, quickly shedding pants, shirt and towel as I run across the warm beach, across the reflective silver plateau of sand separating the water and land. Into the first chilled wave, the next… the next…then plunging head first into a foaming crest, skin tingling with excitement, working hard to pass the surf. Up and over, sown and through, a wave-by-wave struggle that slowly becomes a dialogue, a dance, as my body rolls and tosses. Internal fluids awake. I begin to remember the rhythm, the motion, and then I am with the water; there is no separation. I am as fluid as the waves and for the first time I face the shore and notice the full moon rising above the sea grass.

Now in the shallow water

Rolling, jumping diving, CALLING

Above the sound of waves,

To the sharks,

To the moon,

To the silver plateau of light,

To myself.

YES!

There are some places in this world that I always want to go back to. There is something about them. There is a dialogue, a conversation I want to have.

The End.